15 生物化学分离纯化

生物化学既是本身有科学问题的学科,也含有可以推动其他学科的技术。

生物化学分析生物体内的分子,尚未结束。

生物化学分离纯化生物体系的分子,分析其化学特性和生物学功能,长期以来颠扑不破地对生命科学有重要贡献。

在生物问题的分子水平理解完成之前,在未来很长时期,分析和纯化仍将对生物学研究很重要。本章着重纯化。

生化提纯当然首先应用于生物化学本身的问题,如酶促反应、代谢、信号转导,但也应用于很多其他学科。生化纯化的关键是:有检测生物学活性的方法,获得足量的含有活性的组织、细胞来源,有合适的分离纯化技术和方法。

分离纯化到分子,推动生物学问题的理解。

15.1 生物化学分离纯化的重要性

用的最多的,自然是生物化学领域本身,例如分离到催化特定反应的酶,促进理解代谢。分离到激素,揭示了内分泌的基础。

脑和神经的功能复杂,但其研究在有些方面也得益于生化分离提纯。十九世纪,德国海德堡的Willy Kühne分离视紫红质是视觉研究的里程碑(Kühne,1879,1882),1950至1960年代,美国华盛顿大学Victor Hamburger、Rita Levi-Montalcini、Stanley Cohen分离提纯神经生长因子是发育神经生物学的里程碑、也开启生长因子的研究(Levi-Montalcini and Hamburger,1951,1953;Cohen, Levi-Montalcini and Hamburger,1954;Cohen,1960),并因为带动表皮生长因子的研究而间接促进了癌症研究(Cohen,1962)。分离纯化垂体激素是和神经内分泌的重要工作(Guillemin, 1978; Schally)。分离纯化神经肽是神经传递的重要工作(Euler and Gaddum,1931;Chang and Leeman,1970;Hughes et al., 1975)。分离纯化突触囊泡的膜蛋白,为理解神经递质释放提供了必要基础(Südhof and Jahn,1991)。神经纤维连接的重要问之一是轴突导向(Cajal,1890;Sperry,1963),理解其分子机理的途径之一也是分离提纯(Walter et al., 1987;Luo et al., 1993,1995; Drescher et al., 1995)。

本章先以轴浆转运的生化研究为例,了解分离纯化的基本要素和意义。

再以沅蛋白的为例,说明分离纯化可能带来意想不到的概念。

15.2 轴浆转运的发现和描述

神经细胞,形态看起来与其他细胞很不一样。例如,因为其细胞的突起—神经纤维—可以很长,细胞体在脊髓的神经细胞可以有神经纤维到手指、脚趾,负责合成和代谢的细胞体如何与远距离的神经末梢交换物质,显然是重要的问题。从探索神经纤维的轴浆转运,最后发现是细胞内亚细胞器和分子运动的一个普遍问题,而因此发现的分子机理,也是细胞运动的普适性机理。

最初观察到外周的单纯疱疹病毒可能是沿神经纤维进入中枢神经系统(Goodpasture,1925),注射到大脑的脊髓灰质炎病毒迁移到脊髓可能也是研神经纤维(Fairbrother and Hurst,1930)。神经纤维与细胞体之间切断后,外周部分的神经退变,估计是缺乏细胞体运送来的物质(Cook and Gerard,1931)。

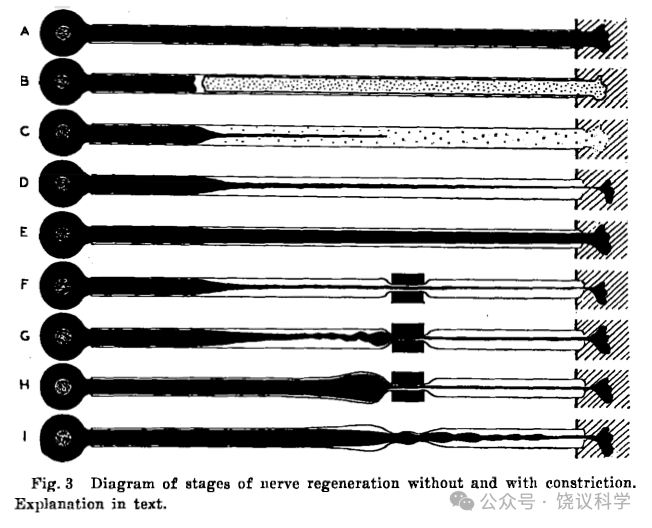

1943年,从奥地利被迫移民美国的犹太生物学家、芝加哥大学的Paul Weiss(1898-1989)观察到:神经结扎的近端物质似乎堆积造成肿大(Weiss and Davis,1943)。他也称之为“筑坝现象”(axon damming)(Weiss and Davis,1943; Weiss,1944a,1944b)。

1948年,Weiss观察再生神经的实验后提出:神经纤维从细胞体长出,其中轴浆运输不仅在生长期间,及时在生长静止期也有轴浆运输,可能运送外周不能合成的如蛋白质(Weiss and Hiscoe,1948)。

注射放射性同位素(32P)后,可以检测细胞体向神经末梢运输磷的速度(每天数毫米),估计磷是以磷酸化蛋白质存在(Samuels et al., 1951;Ochs and Burger,1958;Ochs,Dalrymple and Richards, 1962)。电子显微镜观察到神经结扎端线粒体聚集提示线粒体等细胞器也有轴浆运输(Weiss, Taylor and Pillai,1962;Weiss and Pillai,1962) 。

直接以氚标记的亮氨酸注射后,可以不依赖神经纤维结扎的观察间接推断蛋白质的运输(Droz and Lebolond,1962;Ochs,Dalrymple and Richards, 1962)。

由外周向胞体的运输(逆向运输)也有观察,最早是看见内吞的泡(Hughes;1953),后见胆碱酯酶(Lubińska,1963,1964),肾上腺素(Dahlström and Fuxe,1964;Dahlström,1965),同位素标记的亮氨酸(Lasek,1967),蛋白质(辣根过氧化酶,Kristennson and Olsson,1971),同位素标记的神经生长因子(Hendry et al., 1974)。

到1980年(Grafstein and Forman,1980),已知轴浆转运多种分子(氨基酸、核苷酸、糖等小分子、神经递质、酶等)、细胞器(突触囊泡、线粒体、溶酶体等),和一些外源分子,既有生理意义、也有病理意义。轴浆转运速度分为(Lasek,1982):快速转运(最快每天400毫米,平均每天300毫米,依赖微管和钙离子,需要能量),慢速转运(一种每天0.2到2毫米,一种3、4倍于此,秋水仙碱也能抑制至少一些)。逆向运输速度为正向快速运输的50-70%。

15.3 轴浆转运的机理研究

早期考虑过蠕动为轴浆转运的机制(Weiss,1969)。

1969年,美国洛克菲勒大学的Georg Kreutzberg发现,用秋水仙碱抑制微管蛋白形成微管,结果可以抑制轴浆转运,说明轴浆转运依赖微管(Kreutzberg,1969)。

轴浆转运需要ATP提供能量,而且是沿轴突运输的局部提供(Lux et al., 1970; Dahlström, 1971; Och, 1971)。

到1980年,机制仍然不清楚(Grafstein and Forman,1980;Lasek,1982),提出了一些快速转运的可能机制,如:棘齿机制(转运物质与微管相互作用而被推动),被转运物质被液流裹卷,滑面内质网形成的过程从胞体进入轴突带动。慢速转运的机制,如:蠕动,微管、神经丝与肌动蛋白作用,或者慢速转运是快速转运间或停顿的表象。

1981年,美国达特茅斯学院的Robert Allen(1927-1986)和Woods Hole海洋实验室的井上晋也(Shinya Inoué,1921-2019)独立发明和改进了显微镜下视频录像技术(Allen, Allen and Travis,1981;Inoué,1981)。Allen等用于网足虫,观察到沿微管运动的亚细胞器(Allen, Allen and Travis,1981)。

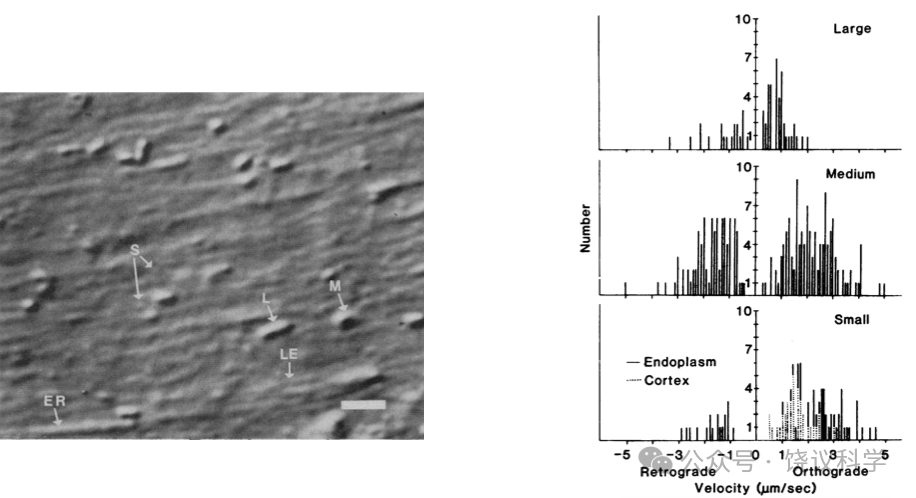

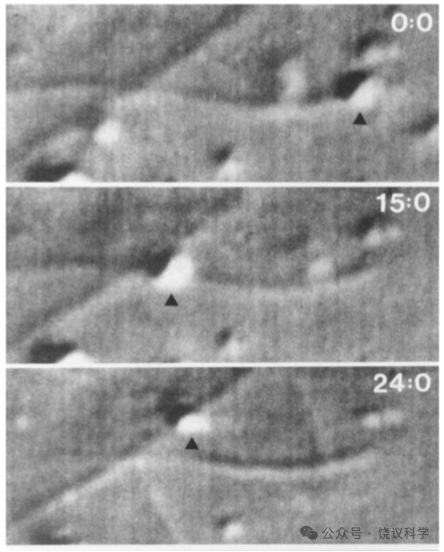

1982年,Allen与合作者直接将其显微录像方法(视频增强反差-微分干涉反差,VEC-DIC)用于枪乌贼巨大神经,观察到沿微管运动的颗粒(Allen et al.,1983)。三类大小不同的囊泡:以前没有观察到的最小(30-50纳米)囊泡,沿线性结构(微管)运动,多半是顺行运输,也有逆向运输,速度可达每秒5微米。中型囊泡0.2到0.6微米直径,大型0.8微米直径。中型和大型运动速度慢些,有停顿和间歇运动。小囊泡的运动和大囊泡在非停顿期都显得是持续运动。

美国西储大学Raymond Lasek实验室依据前人发现枪乌贼巨大神经纤维的轴浆可以像挤牙膏一样挤出来之后还有代谢的特征(Morris and Lasek, 1982),决定把轴浆挤出来之后用Allen的显微录像方法观察转运,结果发现(Brady, Lasek and Allen, 1982):去除细胞膜后单独的轴浆,在玻璃片上看的更清楚,运动不需要细胞膜,同样的线性成分(估计是微管或神经丝)上可以有多个囊泡、不同方向运动,运动需要ATP供能。囊泡在线性成分之外时有布朗运动,而上微管之后沿着线性成分作直线运动,直到在一端掉下后由开始布朗运动(Allen et al., 1983)。

15.4 分离纯化

斯坦福大学的研究生Ronald Vale(1959-)加入Michael Sheetz和Tom Reese的课题组,进一步优化检测方法,之后分离纯化促进运动的蛋白。1985年,他们用五篇《细胞》论文分步发表这一工作。

Vale的父母没有读过大学,母亲是演员、父亲是剧作家,后者需要经常快速写电视连续剧的剧本。他的小学同学包括以后的歌星麦克・杰克逊。但Vale从8岁起就要做科学家,他高中的科研入围了西屋天才奖的前四十位。他在UCSB大学期间从老师那里学到科学的热情可以维持到年老。1980年,他进入斯坦福大学的医学/哲学双博士学位计划。他的研究生导师为神经生物系创系主任Eric Shooter(1924-2018),研究NGF。1982年,他本该转入医学学习阶段,但他被更令人兴奋的研究所吸引,所以他后来再也没有学医,只以自然科学的博士毕业。

Vale的研究生论文(NGF)研究很“高产”,有超出一般学生的文章数量。但他还对其他感兴趣。斯坦福大学的James Spudich(1942-)与当时在康乃狄克大学的Michael Sheetz(1948)合作发表了一篇文章,观察到表面附着肌球蛋白的荧光玻璃珠可以沿来自藻类的肌动蛋白丝运动(Sheetz and Spudich,1983)。Vale想,轴浆转运是否有某种类似的机理(Vale,2012)。他和Spudich决定研究轴浆转运的分子机理。他们本来准备1983年在斯坦福位于加州Monterey的霍普金斯海洋研究站捕捞乌贼,用其巨神经做实验。但那年因为厄尔尼诺现象导致加州海岸抓不到乌贼,他们最后没有办法只好跨美国去麻省的Woods Hole海洋生物学实验室。而NIH的Tom Reese(1945-)和Bruce Schnapp在那里有实验室,光学和电子显微镜技术都非常好。他们四人合作,结果发表于1984年的五篇《细胞》论文,其中四篇Vale为第一作者,一篇Schnapp为第一作者。

首先,Vale等重复把枪乌贼轴浆挤出的实验(Brady, Lasek and Allen, 1982),保持轴浆完整的情况下观察亚细胞器沿“转运丝”(transport filaments)的运动。其次,他们把挤出的轴浆经过载玻片挤压后分离,仍然可以观察到亚细胞器可以沿着丝运动,而且无论亚细胞结构的大小,运动速度都是每秒2.2微米,不同实验、不同次轴突所得轴浆中观察到的运动速度高度一致。不再有快速、中速和慢速轴浆转运的区别,从而认为运动速度只有一个、而且是匀速运动,而在轴突内表观的慢速是因为亚细胞碰到细胞膜减慢速度所致,体积大的慢、体积小的快(Vale, Schnapp, Sheetz and Reese, 1985)。

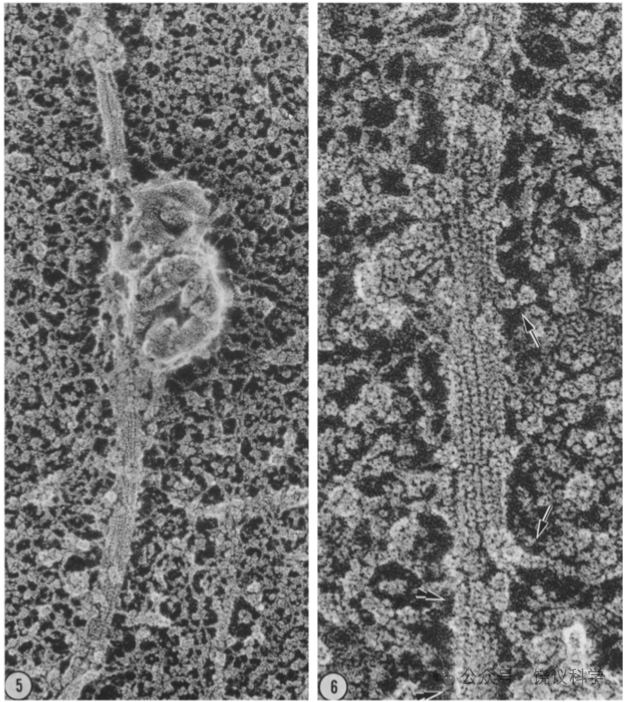

他们进一步的实验确定所谓“转运丝”就是微管(Schnapp, Vale, Sheetz and Reese, 1985)。这是在分离轴浆观察到运动后,用电子显微镜分析转运丝,发现每一根转运丝就是单根微管,而且用抗a-微管蛋白的抗体也验证转运丝是微管。微管是已知对细胞运动重要的管状结构,由微管蛋白多聚化组成的微管每一周微管蛋白数量、微管直径都恒定,在电镜下可识别。

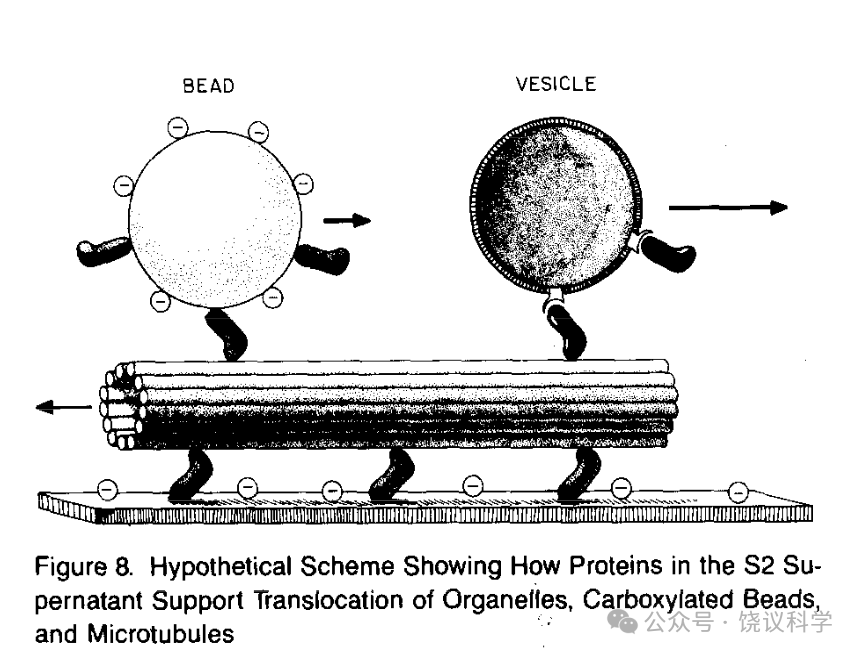

Vale等用前人发明的用乌贼视叶制备微管的办法,制备相对纯化的微管。而把乌贼巨神经轴突的组分分成亚细胞器沉淀部分和轴浆的可溶部分。如果把轴突的亚细胞器部分加到纯化的微管,一般不能观察到亚细胞器的运动,但如果再加入ATP和轴浆的可溶部分,亚细胞器运动显著增加。加入不能水解的ATP类似物AMP-PNP可以抑制这一运动。胰蛋白酶或加热处理亚细胞器组分、或者可溶组分,都可以抑制这一运动,说明两种组分中都有蛋白质参与。把羧基乳胶微球加入,也可以如亚细胞器一样在微管上匀速运动。如果把两个组分和ATP稀释,加到载玻片,可以看到微管也可以运动,玻璃片等于微球或亚细胞器,而与微管的相对运动呈现为微管运动。这些实验成功地把原来在细胞内的运动,在无细胞体系重组,而且可以直接观察微管在载玻片上的运动,不需要观察亚细胞器(Vale, Schnapp,Reese and Sheetz, 1985)。

有了以上体外重组体系,Vale等就以此为功能检测方法,分离纯化促进运动的蛋白质(Vale, Reese and Sheetz, 1985)。为了增强运动蛋白与微管的结合,从而更好分离,他们用AMP-PNP处理样本(乌贼巨神经轴浆或乌贼视球)。结果确实有更多蛋白质与微管结合,然后可以被ATP所释放。在分离纯化过程中见轴浆中约110 kD的蛋白,其行为与运动蛋白一致。在乌贼视球分离过程中,也找到一个110 kD的运动相关蛋白,还有相关的65/70 kD的蛋白质。他们用同样方法,在猪脑也分离到运动相关的120 kD和62 kD蛋白。

他们推测乌贼巨神经轴浆和乌贼视球中110 kD和65/70 kD的蛋白共同组成复合体,为运动蛋白。猪脑120 kD和62 kD蛋白组成运动蛋白的复合体。他们称之为kinesin(驱动蛋白)。

此后,他们意识到kinesin只驱动顺向转运(从细胞体到神经末梢),而不能促进逆向转运(神经末梢到细胞体)。他们制备了抗kinesin蛋白110 kD组分的抗体。如果事先用这一抗体处理巨神经轴浆,移除其结合的110 kD蛋白,轴浆其余组分不促进体外重组系统的顺向转运,但逆向转运活性仍然存在。他们因此认为有不同的蛋白质促进不同方向的运动(Vale et al., 1985)。

美国西南医学中心的Scott Brady再1985年也报道,从鸡脑中分离到130 kD的与微管结合的ATP酶,认为应该是快速轴浆转运相关的蛋白(Brady,1985)。

原本在完整细胞中观察到的运动,最后化简为运动分子推动亚细胞器沿微管运动,深化了细胞生物学的理解。而实验虽然是用神经纤维做的,发现的规律并非神经系统特异的,而是一个基本的细胞生物学过程,神经纤维只是因为长而便于观察,粗而便于开始进行体外无细胞体系的重建。实际上,一开始就可以用其他细胞进行分类纯化,不仅如竞争者Brady用鸡脑,也可以用非神经细胞制备“可溶成分”,依赖功能进行分离纯化。

此后,研究者从线虫和果蝇都分离到微管结合蛋白,从中找到分子量接近、有ATP酶活性、可以促进运动的蛋白质(Lye et al., 1987; Saxon et al., 1988)。在果蝇还制备了抗体(Saxon et al., 1988),结果发现与枪乌贼的kinesin类似(Saxon et al., 1988)。首先是果蝇编码kinesin的基因得以克隆(Yang, Saxton and Boldstein, 1988; Yang, Laymon and Goldstein, 1989)。Vale等分离的现在称为kinesin I,由一条重链(~110 kD)两条轻链(~65 kD)组成。重链的N端为运动端,C端由重链和轻链链接被转运的亚细胞器。现在知道Kinesin是一个家族,人有45个成员(KIFs)。它们将亚细胞器或分子由微管的-端移向+端。家族可以分为14个亚家族,结构不同。它们分布在不同组织细胞,通过转运不同物体而起不同功能。其中一个有趣的功能是在胚胎发育早期,Kif3b参与左右轴的形成。

参考文献

Allen RD, Allen NS and Travis JL (1981). Video-enhanced differential interference contrast (AVEC-DIC) microscopy: a new method capable of analyzing microtubule-related movement in the reticulopodial network of Allogromia laticollaris. Cell Motility 1:291-302.

Allen RD, Metuzals J, Tasaki I, Brady ST and Gilbert SP (1982). Fast axonal transport in squid giant axon. Science218:1127-1128.

Allen RD, Brown DT, Gilbert SP and Fujiwaka H (1983). Transport of vesicles along filaments dissociated from squid axoplasm. Biological Bulletin 765:523.

Brady ST (1985). A novel brain ATPase with properties expected for the fast axonal transport motor. Nature 317:73-75.

Brady ST, Lasek RJ and Allen RD (1982). Fast axonal transport in extruded axoplasm from squid giant axon. Science 278:1129-1131.

Burdwood W (1965). Bidirectional particle movement in neurons. Journal of Cell Biology 27:115A.

Cajal SRy (1890). A quelle epoque apparaissent les expansions des cellules nerveuses de la moëlle épinière du poulet? Anatomischer Anzeiger 21: 606-11; and 22: 631-9.

Chang MM and Leeman SE (1970). Isolation of a sialogogic peptide from bovine hypothalamic tissue and its characterization as substance P. Journal of Biological Chemistry 245:4784-4790.

Cohen S (1960). Purification of a nerve-growth promoting protein from the mouse salivary gland and its neurotoxic antiserum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 46:302-11.

Cohen S (1962). Isolation of a mouse submaxillary gland protein accelerating incisor eruption and eyelid opening in the newborn animal. Journal of Biological Chemistry 237:1535–62.

Cohen S, Levi-Montalcini R and Hamburger V (1954). A nerve growth-stimulating factor isolated from sarcoma 37 and 180. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 40:1014-18.

Cook DD and Gerard RW (1931). The effect of stimulation on the degeneration of a severed peripheral nerve. American Journal of Physiology 97:412-425.

Dahlström A and Fuxe K (1964). A method for the demonstration of adrenergic nerve fibres in peripheral nerves. Zeitschrift für Zellforschung und mikroskopische Anatomie 62:602-607.

Dahlström A (1965). Observations on the accumulation of noradrenalin in the proximal and distal parts of peripheral adrenergic nerves after compression. Journal of Anatomy 99:677-689.

Dahlström A (1971). Axoplasmic transport (with particular respect to adrenergic neurons). Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society (London) Series B 261:325-358.

Drescher U, Kremoser C, Handwerker C, Löschinger J, Noda M and Bonhoeffer F (1995). In vitro guidance of retinal ganglion cell axons by RAGS, a 25 kDa tectal protein related to ligands for Eph receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 82:359-70.

Droz B and Lebolond (1962). Migration of proteins along the axons of the sciatic nerve. Science 137:1047-1048.

Fairbrother R and Hurst E (1930). The pathogenesis of, and propagation of the virus in, experimental poliomyelitis. Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology 33:17-45.

Godina G (1956). L'activite protoplasmique des neurites dans les cultures "in vitro” étudiée par la microcinématographe en contrast de phase. Comptes rendusde l’ Association des Anatomistes 42:582-591.

Goodpasture EW (1925). The axis-cylinders of peripheral nerves as portals of entry to the central nervous system for the virus of Herpes Simplex in experimentally infected rabbits. American Journal of Pathology 1:11-28.

Grafstein B and Forman DS (1980). Intracellular transport in neurons. Physiological Reviews 60:1167-1283.

Guillemin R (1978). Peptides in the brain: the new endocrinology of the neuron. Science 202:390-402.

Hendry IA, Stockel K, Thoenen H and Iverson LL (1974). The retrograde transport of nerve growth factor. Brain Research 68:103-121.

Hughes A (1953). The growth of embryonic neurites. A study on cultures of chick neural tissues. Journal of Anatomy 37:150-162.

Inoué S (1981). Video image processing greatly enhances contrast, quality and speed in polarization-based microscopy. Journal of Cell Biology 89:346-356.

Kerkut GA, Shapira A and Walker RJ (1967). The transport of14C-labelledmaterial from CNS-muscle along a nerve trunk. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology 23:729-748.

Kozminski KG, Johnson KA, Forscher P and Rosenbaum JL (1993). A motility in the eukaryotic flagellum unrelated to flagellar beating. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 90:5519-5523.

Kreutzberg GW (1969). Neuronal dynamics and axonal flow. IV. Blockage of intra-axonal enzyme transport by colchicine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 62:722-728.

Kristennson K and Olsson Y (1971). Retrograde axonal transport of protein. Brain Research 29:363-365.

Kühne W (1879). Chemische Vorgänge in der Netzhaut. Hermann L. eds. Handbuch d. Physiologie d. Sinnesorgane Erster Theil, Gesichtssinn. F.C.W. Vogel Leipzig, Germany.

Kühne W (1882). Beiträge zur Optochemie. Untersuchungen aus dem physiologischen Institute der Universität Heidelberg 4:169-249.

Lasek RJ (1967). Bidirectional transport of radioactivity labelled axoplasmic components. Nature 216:1212-1214.

Lasek R(1968). Axoplasmic transport in cat dorsal root ganglion cells: as studied with 3H-l-leucine. Brain Research 7:360-377.

Lasek R (1982). Translocation of the neuronal cytoskeleton and axonal locomotion. Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society of London B 299, 313-327.

Levi-Montalcini R and Hamburger V (1951). Selective growth stimulating effects of mouse sarcoma on the sensory and sympathetic nervous system of the chick embryo. Journal of Experimental Zoology 116:321–61.

Levi-Montalcini R and Hamburger V (1953). A diffusible agent of mouse sarcoma producing hyperplasia of sympathetic ganglia and hyperneurotization of viscera in the chick embyro. Journal of Experimental Zoology 123:233–287.

Lorenz T and Willard M (1978). Subcellular fractionation of intraaxonally transported polypeptides in the rabbit visual system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 75:505-509.

Lubińska L, Niemierko S, Oderfeld B, Szwarc L and Zelena J (1963). Bidirectional movements of axoplasm in peripheral nerve fibres. Acta Biol exp (Warsz) 23:239-247.

Lubińska L, Niemierko S, Oderfeld-Nowak B and Szwarc L (1964). Behaviour of acetylcholinesterase in isolated nerve segments. Journal of Neurochemistry 11:493-503.

Luo Y, Raible D and Raper JA (1993). Collapsin: a protein in brain that induces the collapse and paralysis of neuronal growth cones. Cell 75:217-27.

Luo Y, Shepherd I, Li J, Renzi MJ, Chang S and Raper JA (1995). A family of molecules related to collapsin in the embryonic chick nervous system. Neuron 14:1131-40.

Lux HD, Schubert P, Kreutzberg GW and Globus A (1970). Excitation and axonal flow: autoradiographic study on motoneurons intracellularly injected with a 3H-amino acid. Experimental Brain Research 10:197-204.

Morris JR and Lasek RK (1982). Stable polymers of the axonal cytoskeleton: the axoplasmic ghost. Journal of Cell Biology 92:192-198.

Ochs S and Burger E (1958). Movement of substance proximo-distally in nerve axons as studied with spinal cord injections of radioactive phosphorus. American Journal of Physiology 194:499-506.

Ochs S, Dalrymple D and Richards G (1962). Axoplasmic flow in ventral root nerve fibers of the cat. Experimental Neurology 5:349-363.

Ochs S (1971). Local supply of energy to the fast axoplasmic transport mechanism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 68:1279-1282.

Paschal BM and Vallee RB (1987). Retrograde transport by the microtubule-associated protein MAP 1C. Nature 330:181-183.

Samuels AJ, Boyarsky LL, Gerard RW, Libet B and Brust M (1951). Distribution, exchange and migration of phosphate compounds in the nervous system. American Journal of Physiology 164:1-5.

Saxton WM, Porter ME, Cohn SA, Scholey JM, Raff EC and McIntosh JR (1988). Drosophila kinesin: characterization of microtubule motility and ATPase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 85:1109-1113.

Schnapp BJ, Vale RD, Sheetz MP and Reese TS (1985). Single microtubules from squid axoplasm support bidirectional movement of organelles. Cell 40: 455-462.

Schally AV (1978). Aspects of hypothalamic regulation of the pituitary gland. Science 202:18-28.

Sheetz MP and Spudich JA (1983). Movement of myosin-coated fluorescent beads on actin cables in vitro. Nature 303:31-35.

Südhof TC and Jahn R (1991). Proteins of synaptic vesicles involved in exocytosis and membrane recycling. Neuron 6:665-677.

Tsukita S and Ishikawa H (1980). The movement of membranous organelles in axons. Journal of Cell Biology 84:513-530.

Vale RD, Schnapp BJ, Sheetz MP and Reese TS (1985). Movement of organelles along filaments dissociated from the axoplasm of the squid giant axon. Cell 40: 449-454.

Vale RD, Schnapp BJ, Reese TS and Sheetz MP (1985). Organelle, bead and microtubule translocations promoted by soluble factors form the squid giant axon. Cell 40: 559-569.

Vale RD, Reese TS and Sheetz MP (1985). Identification of a novel force generating protein, kinesin, involved in microtubule-based motility. Cell 42:39-50.

Vale RD, Schnapp BJ, Mitchison T, Steuer E, Reese TS and Sheetz MP (1985). Different axoplasmic proteins generate movement in opposite directions along microtubulesin vitro. Cell 43: 623-632.

Vale RD (2003). The molecular motor toolbox for intracellular transport. Cell 112:467-480.

Vale RD (2012). How lucky can one be? A perspective from a young scientist at the right place at the right time. Nature Medicine 10:1486-1488.

Van Breemen VL, Anderson E and Reger JF (1958). An attempt to determine the origin of synaptic vesicles. Experimental Cell Research (Supplement) 5:153-167.

Walter J, Kern-Veits B, Huf J, Stolze B and Bonhoeffer F (1987). Recognition of position-specific properties of tectal cerll membranes by retinal axons in vitro. Development 101:685-96.

Watson WE (1968). Centripetal passage of labelled molecules along mammalian motor axons. Journal of Physiology196:122-123P.

Weiss P (1943). Nerve regeneration in the rat, following tubular splicing of severed nerves. Archives of Surgery 46, 525-547.

Weiss P(1944a). Damming of axoplasm in constricted nerve: a sign of perpetual growth in nerve fibers. Anatomical Records 88 (Supplement):464.

Weiss P (1944b). Evidence of perpetual proximo-distal growth of nerve fibers. Biological Bulletin 87:160.

Weiss PA (1969). Neuronaldynamics and neuroplasmic (“axonal”) flow. Symposium of the International Society of Cell Biology 8:3-34.

Weiss P and Davis H (1943). Pressure block in nerves provided with arterial sleeves. Journal of Neurophysioogyl 6:269-286.

Weiss P and Hiscoe HB (1948). Experiments on the mechanism of nerve growth. Journal of Experimental Zoology 107:315-395.

Weiss P, Taylor AC and Pillai PA (1962). The nerve fiber as a system in continuous flow: microcinematographic and electromicroscopic demonstrations. Science 136:330.

Weiss P and Pillai PA (1962). Convection and fate of mitochondria in nerve fibers: axonal flow as vehicle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 54:48-56.

Yang JT, Saxton WM and Boldstein LSB (1988). Isolation and characterization of the gene encoding the heavy chain of Drosophila kinesin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 85:1864-1868.

Yang JT, Laymon RA and Goldstein LSB(1989). A three-domain structure of kinesin heavy chain revealed by DNA sequence and microtubule binding analyses. Cell 56:879-889.

Zelena J and Lubińska L (1962). Early changes in the acetylcholinesterase activity near the lesion in crushed nerves. Physiologia bohemoslov 11:261-268.